Remembering the Japanese American Internment

The Japanese first came to the Pacific Northwest in the 19th century to help meet the demand for labor, working in sawmills and strawberry fields. By the 1930’s more than half of the Nikkei (first generation Japanese Americans born on American soil) in the United States lived in the Pacific Northwest.

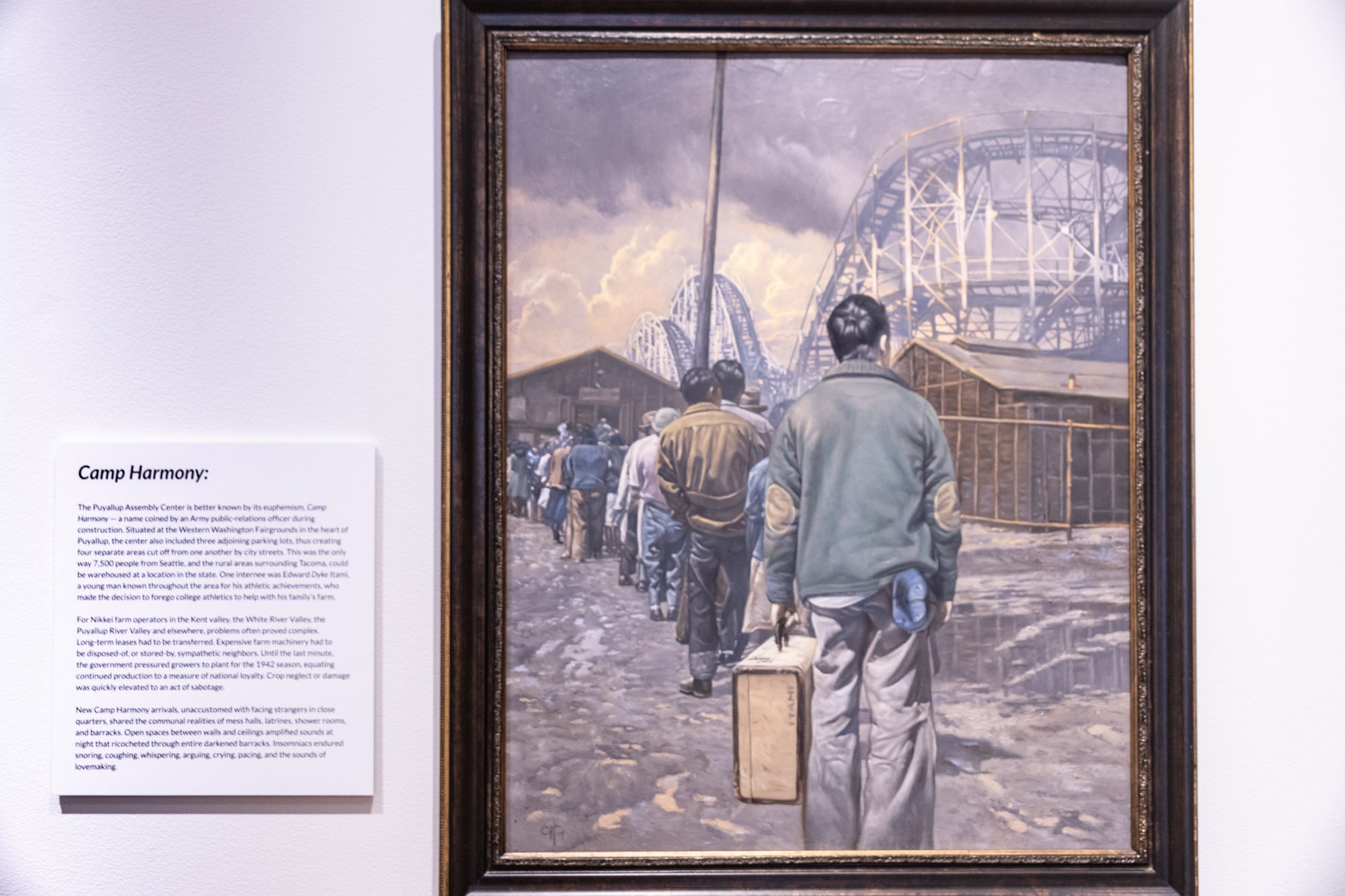

The bombing of Pearl Harbor by Japan on December 7, 1941, incited one of the most racially charged violations of the U.S. Constitution in America’s history. Executive Order 9066, issued by President Franklin Roosevelt on February 19, 1942, authorized the evacuation of all persons deemed a threat to national security from the West Coast. Because of their proximity to naval bases, the Japanese Americans from Bainbridge Island were the first group in the U.S. to be evacuated. They were interned at the Manzanar Relocation Center in Central California prior to being sent to the Minidoka Relocation Center in southern Idaho. Those from Seattle and Alaska were sent to the Puyallup Assembly Center, also known as Camp Harmony, located on the current Western Washington Fairground property.

After the war, many Nikkei returned to the Pacific Northwest and picked up their lives where they left off. It wasn’t until the 1960’s and 1970’s with the civil rights movement and the growth of Japanese American activism that the expulsion received serious attention. In 1976, on the thirty-fourth anniversary of Executive Order 9066, President Gerald Ford declared the evacuation a "national mistake”, and in 1988 HR 442 was signed into law by President Ronald Reagan providing for reparations for those who survived.

Panama Hotel – Chinatown International District

I was first introduced to the Panama Hotel many years ago as I read the book Hotel on the Corner of Bitter and Sweet by Jamie Ford, a historical romance novel about the relationship between Henry, a Chinese American boy and Keiko, a Japanese American girl, who met in elementary school. You’ll have to read it yourself to find out the ending. The hotel was built in 1910 by Seattle’s first Japanese architect Saburo Ozasa. It was originally designed to be a rooming house for single men and became an important part of the neighborhood, in Japanese known as Nihonmachi. Years later the hotel, having been boarded up for decades, was discovered to contain the belongings of many families who had been sent to internment camps and never returned to claim their goods.

The romance novel may be fiction, but the hotel is real. It has become a popular tea (and coffee) house having on display many of the relics that remain from families that did not return to Seattle from the camps. It is still a small hotel, but the charm is on the main floor and the floor below where personal belongings and photos are on display. My favorite is a blueprint which contains the names and locations of the families that lived in the neighborhood. The hotel became a National Historic Landmark in 2006, and in 2015 was designated a National Treasure by the National Trust for Historic Preservation. Jan Johnson, the current owner who bought the hotel in 1985, is working with the Trust to find just the right people to purchase and preserve this treasure.

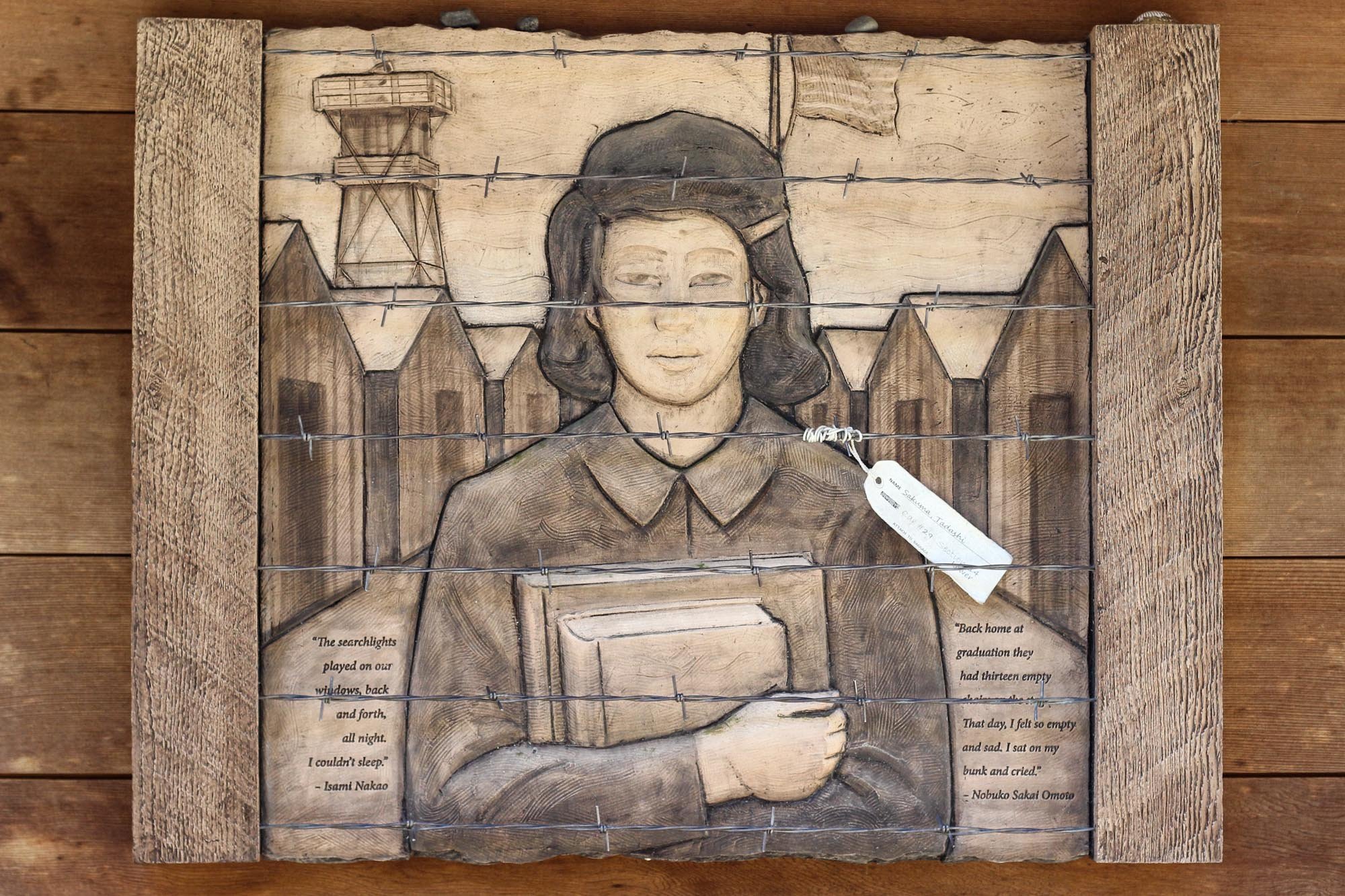

Johnson collaborated with Zocalo Studio to produce a Memory Wall outside the Panama Hotel representing the internment period and to bring outside what is inside the hotel to be more public.

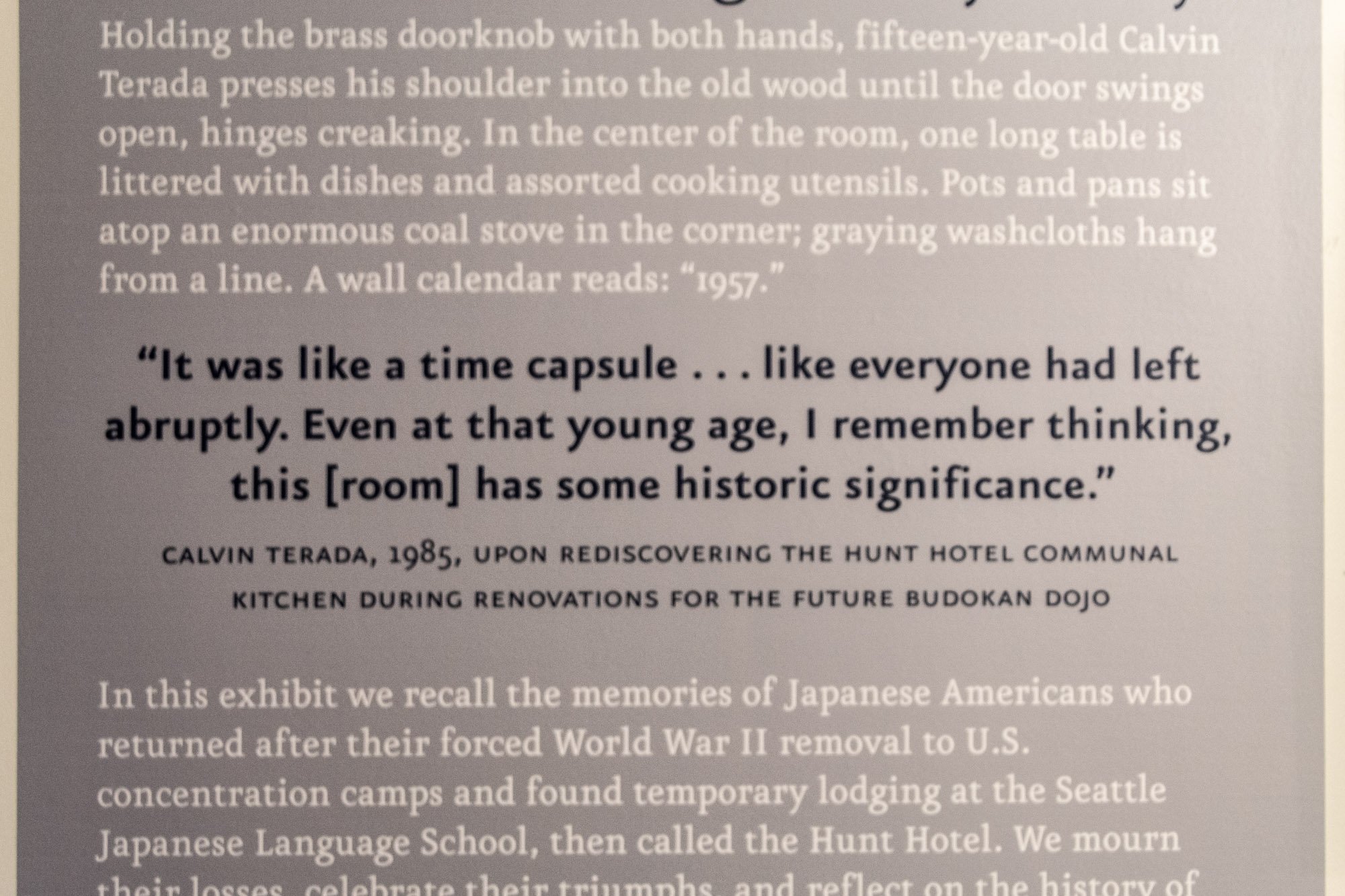

Japanese Culture & Community Center of Washington

The Nikkei Association of Washington and the Japanese Language School merged in 2008 to form this important organization, its home located in the eastern edge of the Chinatown International District. I was impressed with what I found there related to the Japanese American internment. I was led down several hallways to see all the treasures, including crafts that had been made at the internment camps. This building, known as Hunt Hotel following the release of the internees, served as transitional housing for many people that had no place to live when they returned from the Minidoka internment camp. Minidoka was otherwise known as Hunt Camp for its proximity to Hunt, Idaho. As part of an exhibit, Unsettled/Resettled: Seattle’s Hunt Hostel, (sometimes called Hunt Hotel) posters tell stories of the residents before the war, during the war and after the war. It’s absolutely eye opening.

I also spent a lot of time reading a large display that told the story of Gengi Mihara, An IsseiPioneer (a first-generation Japanese immigrant). He was a Seattle business owner, a charity worker, and a leader in the Japanese American community. The display includes family photos, poems he wrote to his wife, and a piece of his luggage along with an American flag. Videos are included in both links which make this story even more compelling.

INS Building

Now known as INScape Arts, the former US Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) building was constructed in 1932 as the entry and exit point for immigrants arriving in Seattle, hundreds of whom were detained there for months. Once the Pearl Harbor bombing occurred in 1941, its focus became detention for first generation Japanese community and businessmen. The five- story building had detention cells, a cafeteria, a hospital, an immigration court and administrative functions. Because they were unable to be deported back to Japan many of the detainees remained here for months prior to being transported to internment camps.

This Mediterranean Revival style building with Corinthian columns now houses 125 artists as places for them to work and showcase their bounties. In 2014 the Wing Luke Asian Museum partnered with INScape Arts and created “Voices of the Immigration Station: 72 Years of History on Five Floors,” a permanent art installation that marks significant locations in the facility, and using a variety of media, features images from before the building was transformed. Each room’s previous use is marked with signs, so history is not forgotten. I look forward to exploring this building once Covid restrictions are lifted and the public can again visit.

Bellevue Arts Museum

Emerging Radiance: Honoring the Nikkei Farmers of Bellevue. Having lived in Bellevue for 25 years I knew that much of the area had been farmland. However, I don’t recall that it was ever mentioned that this was where Japanese Americans lived and worked.

Michelle Kumata, a local Japanese artist with a gallery in the CID, created a mural and immersive storytelling experience that relayed experiences of Japanese American farmers who lived in Bellevue from 1920–1942 and were taken from their homes to be incarcerated. Using QR codes, Spark AR augmented reality Instagram filters were used so visitors could "meet" the actual subjects as they share in their own words their connections to the land before WWII, during incarceration, and post-WWII. This mural which educated the public about the history of both the land and the people was only publicly on display temporarily. Having been sponsored by Meta Open Arts, the original mural is on display at Meta’s Bellevue offices.

Bainbridge Island Japanese American Exclusion Memorial

The Japanese American Exclusion Memorial, located on Bainbridge Island, was dedicated in 2011 on the site of the former Eagledale ferry dock at Pritchard Park, where on March 30, 1942, 226 Japanese Americans boarded the ferry to a nameless destination. The memorial is set in an old-growth forest with lovely walking paths that wind down to the dock. Its long wall, containing the names of all 226 Japanese American Bainbridge residents, is made of old growth red cedar, granite and basalt. Friezes throughout depict scenes of the exclusion, including people being herded onto the ferries. I have visited the memorial several times and find it to be emotionally impactful as I discover new images each time.

Bainbridge Island Museum of Art

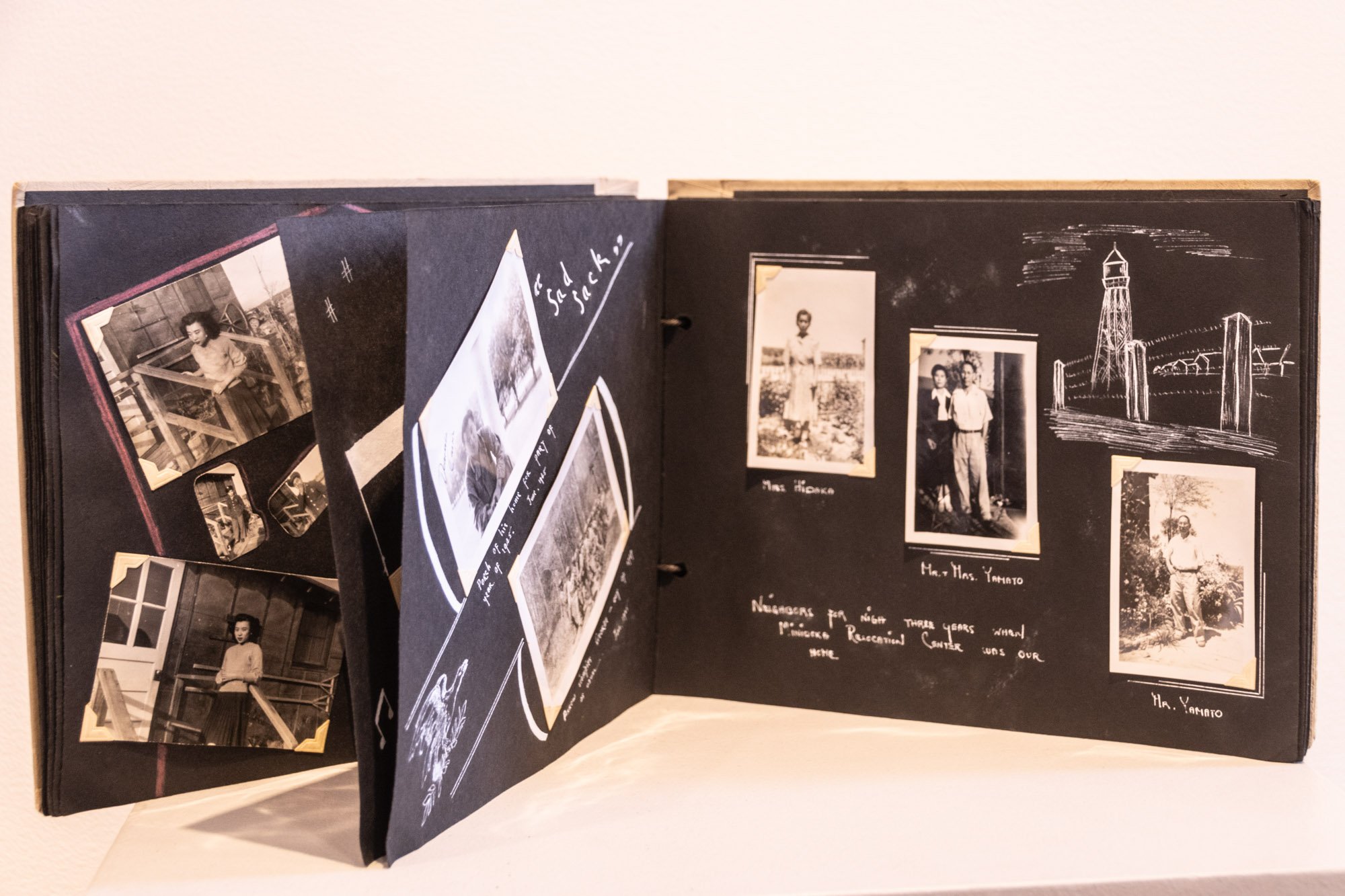

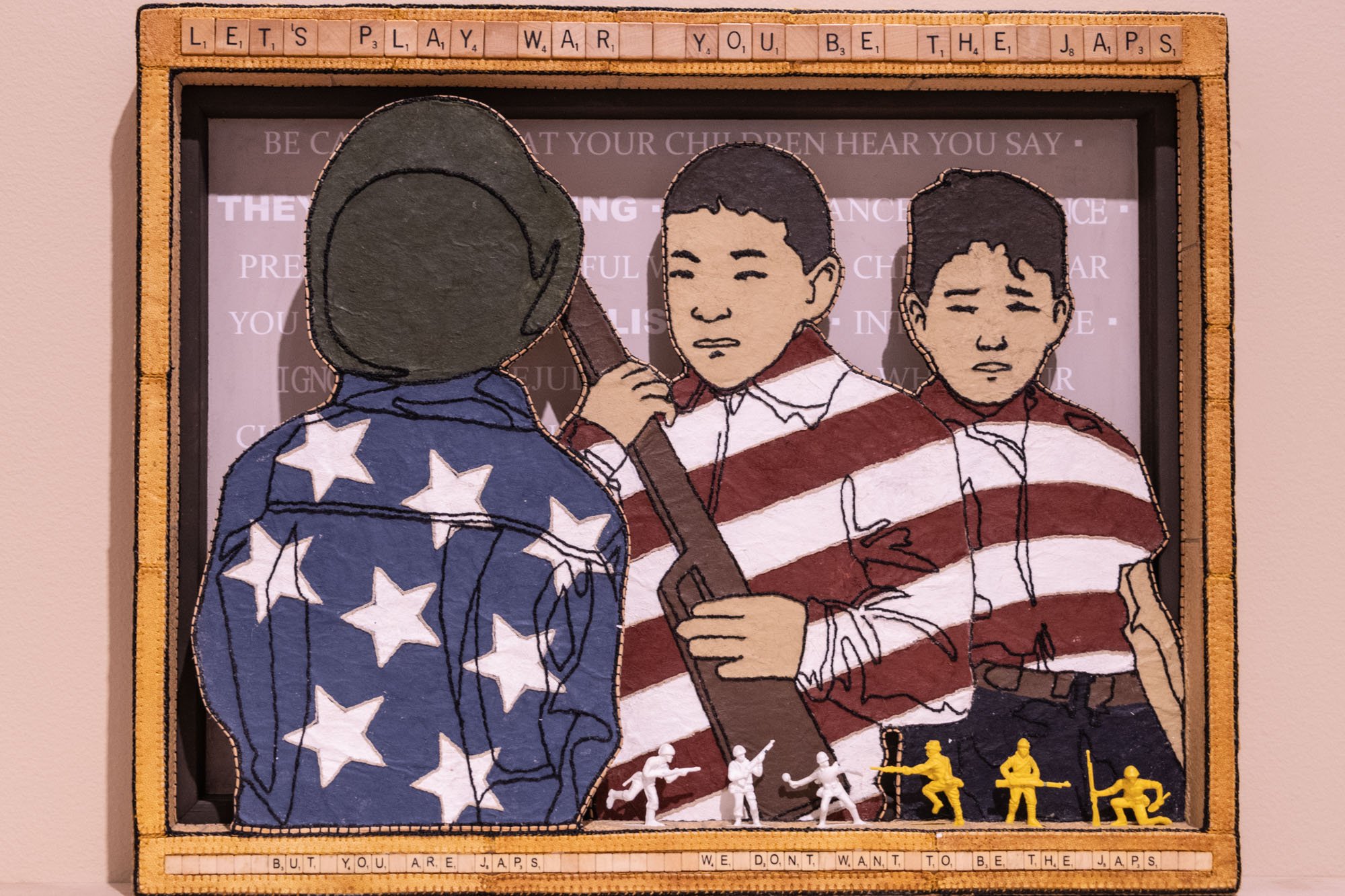

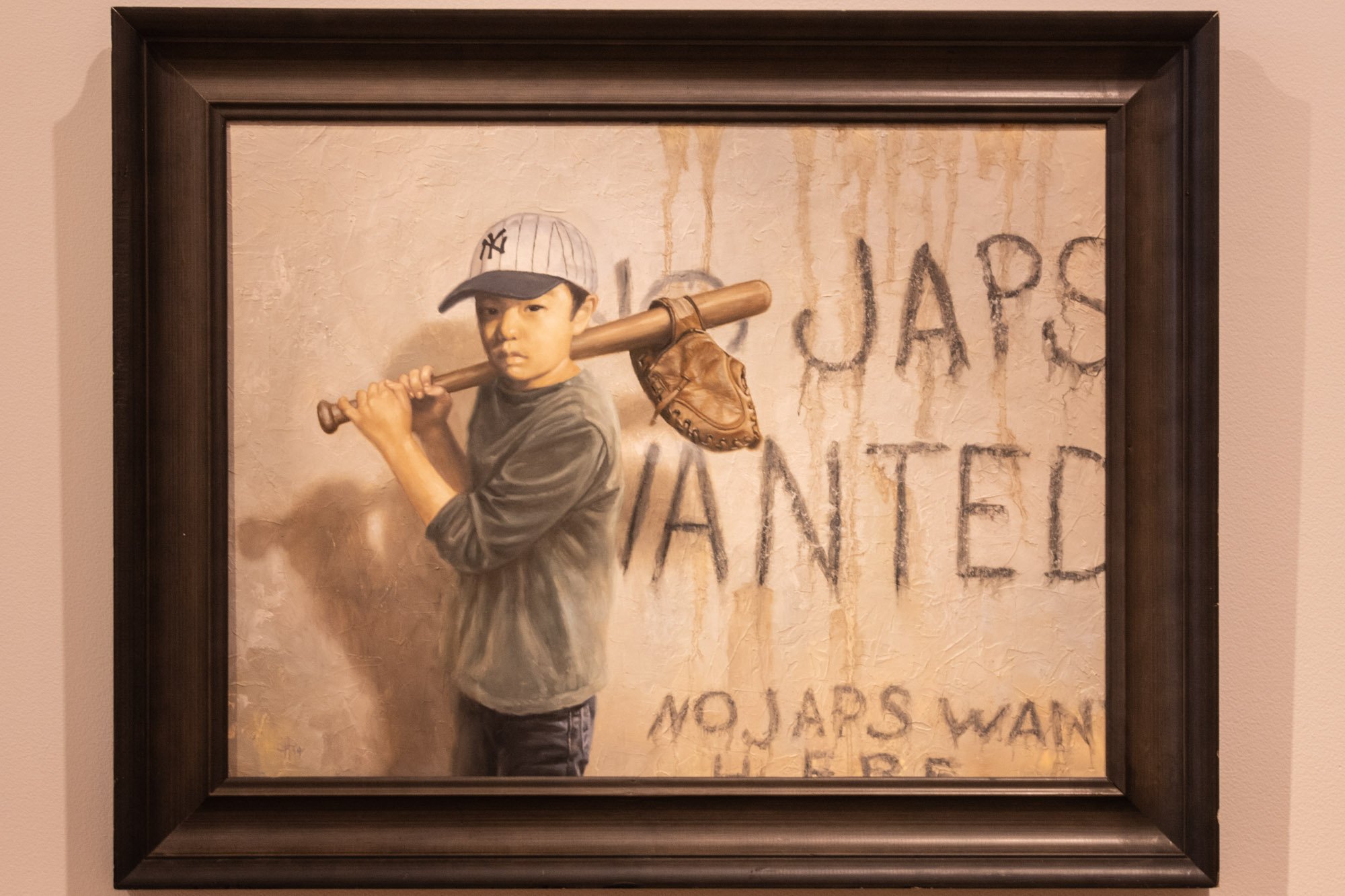

Americans Incarcerated: A Family’s Story of Social Injustice, at the Bainbridge Island Museum of Art, from March 11 – June 12, 2022, is a collaboration between Jan and Chris Hopkins, from Everett, Washington, to memorialize the eviction of Japanese Americans during World War II. Jan’s parents who had been interned, met at Camp Harmony, the temporary processing facility at the Puyallup Fairgrounds, yet Jan had little knowledge of her heritage or what her family had gone through. The exhibit contains Chris’s works in oil, Sumi ink and charcoal, and Jan’s sculptures and mixed media as well as actual pieces from those interned such as scrap books, photographs and even a child’s violin. The paintings, in particular, are so life like that I felt an emotional connection with each one of them. They were not easy to walk past without stopping and thinking about the subjects’ experiences.

Bainbridge Island Historical Museum

“Kodomo No Tame Ni—For the Sake of the Children.” is award winning exhibit that covers a century of history of pioneering Japanese immigrants and Japanese Americans on Bainbridge Island from 1883 to 1983, highlighting their contributions to the community, businesses, and culture and sharing their experiences and perspectives during World War II. Under normal circumstances this museum has a vast collection of items, videos, photos, and oral histories related to the Japanese American internment. However, this collection is not available during their extensive remodel which is expected to be completed later in the spring this year. I was able to peak into their research library and saw many document collections related to this time in history.

This post highlights some of the many locations in Seattle and on Bainbridge Island that focus on the history of the Japanese American incarceration during World War II. They provide incredible images of the experiences of these people and remind us of the impact the incarceration had on them at that time. During March, several events will take place on Bainbridge Island to remember the very first evacuation.